The content strategy of civil discourse, part 1

Here’s a fun experiment. Show an audience the following photo and ask…

“Should this person drive this car?”

What you’ll get is a policy discussion.

“Of course not! Old people are bad at everything!”

“That’s ageist! People should be able to do what they want!”

All you will learn at the end of that conversation is who is on what side.

Show that same photo to a different audience and ask…

“How might this person drive this car?”

What you’ll get is a design discussion.

“What if we moved the steering wheel?”

“What if we had a heads up display on the dashboard?”

What you will learn by the end of that conversation are several different ways a senior citizen might be able to drive a car.

Online, we have become very good at the first conversation. We can debate “should” all the live long day. And it’s very easy to use the web to find out who is on what side.

What we’re not as good at is having the “how” conversation. And the platforms we have aren’t necessarily optimized for that kind of discussion.

What I’d like to talk about in this series is how to have that “how” conversation and hopefully make the web a better place for it.

The above example comes from David Bornstein who, with Tina Rosenberg, co-founded the Solutions Journalism Network. Their point is that journalism has gotten very good at the should story. Calling out bad behavior—which is a vital function of journalism, but not the only one.

They point out that there is also the need for the how story. How did that one college come to lead the U.S. in African-American graduates? How did that one business help to revitalize a town? What are the positive outliers in society and what is repeatable about how they became positive outliers?

Another group doing work in this area is the Convergence Center for Policy Resolution, whose founder, Robert Fersh, had this to say about why he founded the organization.

“Over a period of years I kept meeting people of great decency who had different world views. But there wasn’t a place where they could meet to bring out the best in each other and find answers that each hadn’t considered.”

There are a few phrases in there that are worth considering.

“People of great decency.” I think that we assume that the people who disagree with us, by nature, have no decency. If they did, they’d agree with us, right?

“Wasn’t a place.” As we’ll see in this series, environment matters. You need a place to have these kinds of conversations that are suited to and encourages these conversations. Just any old place won’t do.

“Best in each other.” Again, often we assume that there is no “best” to be found in people who disagree with us, but that is not necessarily the case.

“Hadn’t considered.” This is perhaps the most key. We assume that we know it all. That we’ve already considered all of the important variables (or that we know which variables are important). That the solution or position we’ve arrived at is the perfect one and that there is nothing new to learn. This is a mistake.

None of this should be a surprise. The types of environments we have to have these conversations these days look something like this…

This is Thunderdome. “Two men enter. One man leaves.” We assume that political discourse is meant to be a zero-sum game. There will be a winner and a loser. There will be no middle-ground solutions.

Part of the reason we make this assumption is the Fundamental Attribution Error, a cognitive bias that basically boils down to, “I’m OK. You’re terrible.”

If you see somebody run a red light your first instinct might be to imagine they’re some sort of scofflaw—an impatient, terrible driver. If you run a red light your first instinct might be to say, “Well, I was late. I had to get to the hospital. The person behind me was honking at me.” You attribute the bad behavior of the other driver to something about them personally, something internal. You attribute your own bad behavior to circumstance, something external. It never occurs to you that they might be the ones running late but are, in and of themselves, perfectly fine human beings.

In an episode of the You Are Not So Smart podcast, host David McRaney uses a George Carlin joke to illustrate Naive Realism, the root from which this error grows.

“Anybody who drives slower than you is an idiot. Anybody who drives faster than you is a lunatic.”

His guest, Lee Ross, finds a disturbing parallel to politics. Anybody more conservative than you is a hick, backwards, wants-it-to-be-1950’s racist. Anybody more liberal than you is a hippy-dippy, idiotic, wants-it-to-be-1960’s communist. But you, you’ve got it all worked out. You’re God’s perfect little creature. If only everybody would just listen to you…

With that attitude, is it any wonder we can’t find common ground?

In lieu of finding common ground, we tend to opt for outrage.

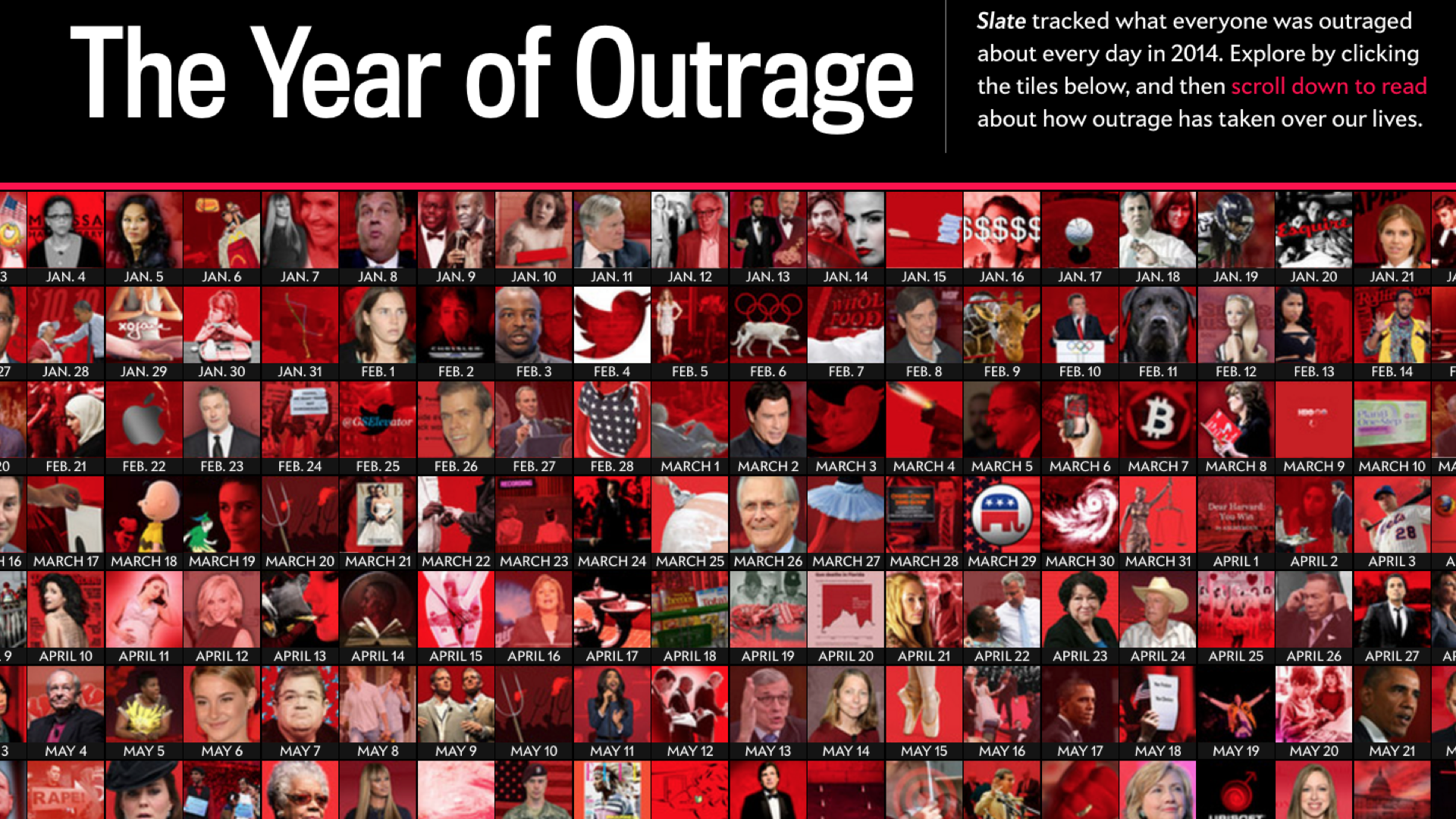

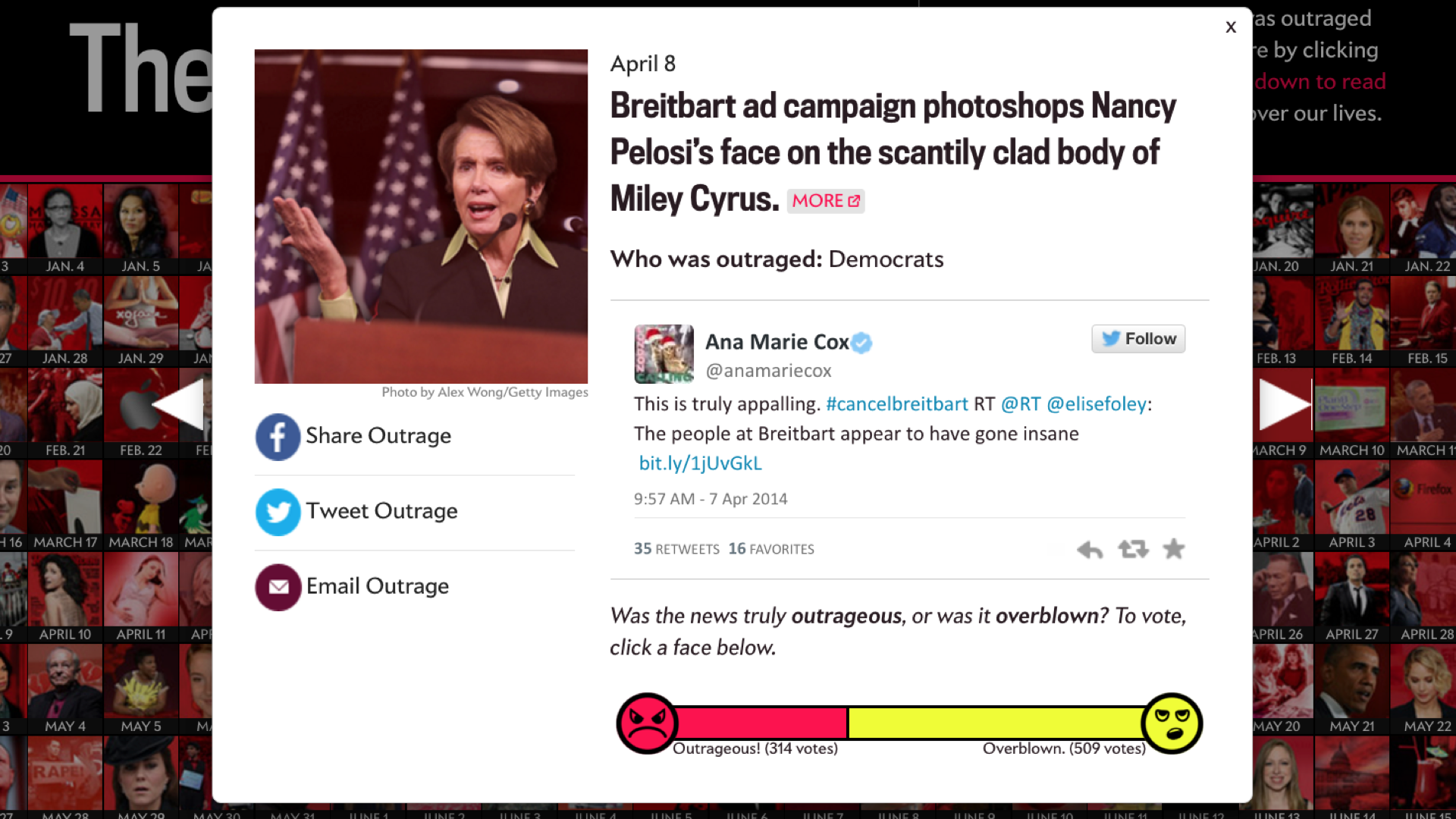

This, believe it or not, predates the Trump Administration. In 2014 Slate created a sort of advent calendar of outrage that allowed you to click on any date for the year and find something that Twitter was losing its mind over. To wit…

You could literally throw a rock at a calendar and find an argument. Put another way…

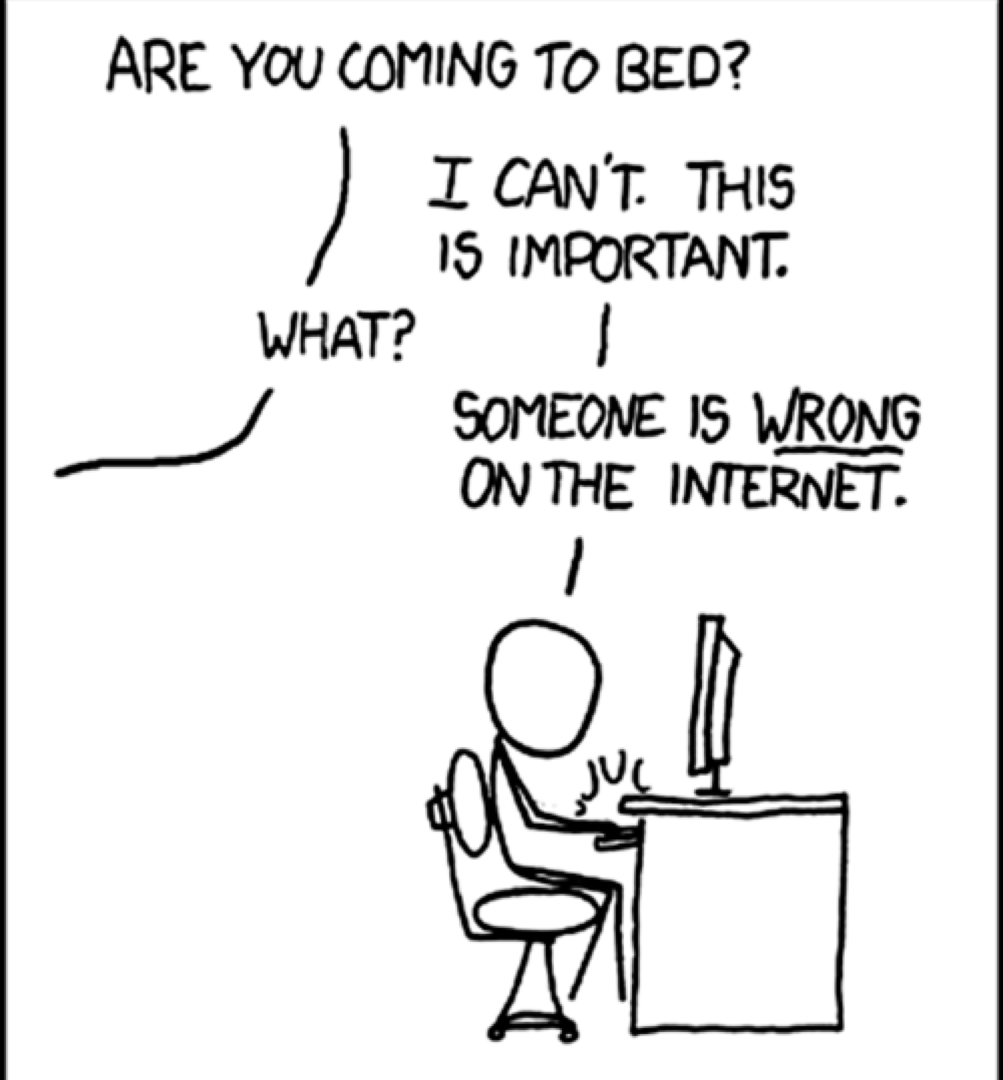

If aliens had to derive the purpose of the internet based on human behavior it would look something like this: The internet is where you go to find people who are doing it wrong and tell them they’re doing it wrong.

Remember this?

This is especially relevant now that this has escalated from weird hashtags to actual police involvement, but the basic idea was that your barista would write the phrase “#RaceTogether” on your coffee cup and then…you’d talk to them about Rodney King? I don’t know. I don’t know what they thought was supposed to happen. But what did happen was Twitter lost they damn mind.

As well they should—it’s a terrible, tone-deaf idea. But here’s the thing. At no point did we ask, “Well, what would a productive conversation about race actually look like?” If we could agree to that, then we could start discussing how to build one.

And here’s the thing, you could have a conversation as the product. Journalist Ronnie Polaneczky set up a sign and two chairs in a park in downtown Philly. The sign said…

I WILL LISTEN

WITH COMPASSION, WITHOUT JUDGEMENT, WITH AN OPEN HEART

SO:

IS THERE SOMETHING YOU NEED TO SAY?

TELL ME

I WILL LISTEN

And sure enough, person after person sat down and unburdened themselves. Often, she said, folks would sit down saying, “I won’t take but a moment of your time,” and then one hour later they were still talking.

Clearly there is a need here, it’s just a question of how best to frame it.

In part two, we’ll talk about some of our misconceptions about how we got here.

Did you know Think Company offers this series as a talk for teams, events, and conferences? If you’re interested in learning more, get in touch with us via our contact form.