Experience Review: The BMW Guggenheim Lab

I’ve been told that I missed my calling as a theatre critic. Most people walk out of shows and say, “Well that was nice. Where should we go for dessert?” Not me. I’m that person who feels compelled to comment on every aspect of the experience, be it good or bad. E-ver-y-thing. That’s probably why I work here.

I was in Manhattan the other weekend and stopped by to check out the BMW Guggenheim Lab, a “mobile laboratory traveling around the world to inspire innovative ideas for urban life.” While it might not be theatre, it is in fact a stage – with the singular purpose of inviting the audience up onto it to collectively brainstorm ideas for the improvement of urban life; a complex design problem if ever there was one.

So how did it fare? Here’s my official, unofficial review:

Um, Hello?

Entering from Houston street, the BMW Guggenheim Lab has a nice beer garden feel with trees and picnic tables and a chalkboard out front listing the day’s program offerings. We happened to arrive while a program was underway and found ourselves awkwardly waffling outside, debating between “crashing” the program by walking in or turning around and leaving. Uncertainty led to a sense of unwelcome in a matter of seconds.

Walk into any good restaurant and someone’s there to greet you, make you feel welcome and inspire confidence that this is a place where you want to spend the next hour or so of your life, and you’re not going to get food poisoning. There was no analogue here, compounded by the fact that as a visitor you aren’t entirely clear what the “lab” even is. What kind of experience will it provide? Will it be entertaining? Are you going to learn anything? Is anything going to be asked of you? How long will it take? Where should you go first? Is it OK to just walk in?

We stood outside feeling mildly like peeping toms with these and other questions in our heads until I (seeing the glimmer of a blog post) mustered the courage to crash the party and walk in.

Climbing Over Chairs Is For Weddings

The act of walking in was, in itself, a feat. The front of the space was loaded with long tables with people huddled around them all engrossed in discussions having something to do with maps and colored pens (we never learned what was going on there). But to get in, we had to weave through this obstacle course of legs and bags and chairs to arrive at the only landmark I could make out as an official place for information: a podium, with a person standing at it. Once I reached her, I mumbled something like, “Sorry… is this okay?” I felt like I was interrupting. Like I was in the way.

On the one hand, a crowded room of people earnestly talking about something is a really exciting thing to experience, but it fails if you don’t feel like there’s room metaphorically or even physically for you to join in.

A Breath Of Fresh Air

Next, we crossed a threshold that visually divides the space and entered a completely different realm. It was open and airy, with people comfortably standing around what appeared to be a chessboard on the floor with sculptural game pieces on it. It was like emerging from a stuffy, loud banquet room onto a cool veranda where the people you really want to spend time with are hanging out.

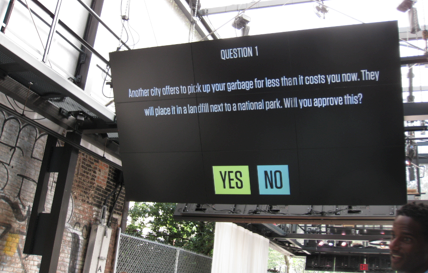

We were immediately engaged by a staff person inviting us to play a game. The game is called Urbanology and you can play it on the Lab’s website. But what works about it as a live experience is exactly what makes it lackluster as an online experience. Briefly, Urbanology asks participants 10 yes/no questions on a variety of topics having to do with urban life. People manning the game pieces (representing innovation, transportation, health, affordability, wealth, lifestyle, sustainability and livability) are asked to respond with their particular issue in mind. For each question, the majority vote wins and the various game pieces either advance or fall back as a result of the vote. Along the way, you’re shown the ratio of total votes in favor or against the question that your group just answered. The game ends by likening the city you’ve created based on the final distribution of the issues on the board to real cities around the globe with similar issue prioritization.

What was more fascinating than the game or its results (and why Urbanology as an online single-player game falls short) was how a group of strangers played it together. Of the approximately 15 people participating, we had a very wide cross-section of ages, races and ethnicities and I’m certain a host of other variables not easily discernible on the surface. Everyone quickly got into the game. They offered explanations for their votes. They asked questions of each other. They tried to persuade others to see the issue from their perspective. They shared what is important to them. They listened respectfully. They engaged. They gave thought to their position on issues they may have never considered before. They learned that others, people they might assume were much like them, hold completely different opinions. They laughed. They agreed to disagree. And they respected the majority vote as final. It was democracy in action – albeit a no-stakes version. Nevertheless, it was a refreshing experience, and reminded me a heck of a lot of the way we design Think Sessions to work.

Unsolicited Design Advice

I can’t say that what I took away from Urbanology was the intended “lesson.” Given the stated purpose of the Lab, my guess is no. But that’s the beauty of a stage after all, you put something up there and it’s up to the individual audience member to decide what, if anything, they’ll take away from it.

Ultimately, I’d say it was a worthwhile experience cooked up by organizations we admire (though you might want to revisit that website design, guys…) – but if I might make a suggestion: flip the spaces. Use the game as the entry point, engaging people around the fun they might have spending more time with and learning from the strangers around them. Then invite those who are hungry for more into the “serious table space” where they can roll up their sleeves, sketch ideas, build off of each other, and – without even being aware of it – participate in the early stages of what is the core of the design process: identifying problems, casting visions, observing and asking, and brainstorming solutions together – another important aspect of democracy in action.