SXSW 2020: How AI poses challenges to authorship

On March 17, I will speak at SXSW 2020, in the Fantastic Futures track, on the challenges that AI poses to authorship as we conceive of it. The talk is based on my experience with giving a Markov bot access to all of my Facebook posts since 2005 to write a series of poems mimicking my own voice. Markov bots infer the probability of a sequence. They are often used for automated pattern recognition, and speech is, of course, a grand pattern.

I submitted the bot-written poetry for publication and was published, leading to the fundamental question: who was the author?

Intro to AI and NLP

The term “AI” has become a bit of a vague bogeyman. It’s often presented as a catch-all term for a large category of systems that attempt to derive insights from patterns processed in large datasets. Natural language processing (NLP) is a branch of artificial intelligence that helps computers understand, interpret, and manipulate human language.

To create a well-formed sentence that we can easily understand—its intent, its tone, and so forth—we feed machines gobs (not the technical term) of data in the form of conversations (or sonnets or haikus) and teach them to speak. As we continue to train computers to become more “natural,” “more organic sounding,” and frankly, “more human,” we continue to introduce challenges around authenticity and trust—challenges that cut to the very core of what makes us unique as humans.

Does authenticity matter? Should something be trusted more or less if made by a person? If something is created by a computer, and we’re told such, do we give it more credence? If a poem is written by a computer, should it be less meaningful?

What Would I Say?

In 2014—before I lost trust in social media, before Cambridge Analytica used my answers to “Which Disney Princess Are You?” Buzzfeed-style quizzes to hyper target me—I gave a Markov bot access to all of my posts. I would not do this again today.

During this time, there was a burgeoning world of developers toying with Facebook as a platform. Facebook was offering new conveniences like the one sign-on (proprietarily known as Facebook Login) which let users bypass the creation of entirely new usernames and passwords, in favor of their already existing Facebook logins. No new credentials needed, a few clicks saved. This small user convenience granted developers a wide array of data associated with one’s profile. Facebook also began offering developers the ability to create third-party applications to be used on the social network’s platform. Those apps and services often gained access to user’s data once installed. They also used Facebook’s single-sign on feature.

One of the apps created during the halcyon days of this data goldrush was called What Would I Say? This bot is now defunct and is in violation of Facebook’s since updated Terms of Service. It automatically generated posts that sounded like you! Your similar tone. Your similar voice. Your similar lexicon. It was similar to “you” because it read your past status posts. Using your post history as its corpus, the developers trained a Markov bot on a mixture model of bigram and unigram probabilities.

The sentences generated by the Markov chain were random, but comprised of a sequence of possible words in which the probability of each word depended only on the previous one. This bot, created in 2013, also pales in comparison to how advanced our Natural Language Processing tools are today. Its output was often questionable. There were myriad issues in grammatical structures and its use of punctuation often led to never ending run-on sentences with no clauses. This bot was important though, as its ubiquity marks one of the first times many people had access to an overt form of NLP artificial intelligence.

The Bot Poems

I fed the “What Would I Say?” Facebook application all of my posts from 2005 through 2013. Eight years. Thousands of sentences. So many of my emotions. Every public update on how I was feeling. All of my embarrassing oversharing. I wove the bot’s responses, line by line, status-by-status, into a series of poems. I didn’t recognize the output. The words were mine but the memories weren’t. The poems were lucid and strange. Like a Dali painting transposed. Nonetheless, I submitted this experiment to several literary magazines and was eventually published by Punchnels. Here’s one of those poems:

#wwis three

I have breast plate armor; ermine fur collar, broadsword, black sun.

Getting ready for the genius child;

busy working water and Chantilly Lace.

This is incredibly blessed to fail.

Why yes, I am going to die of something

on an ulterior avenue.

I’m usually elated after publication. I’m excited that others will read my works, but I’m also hopeful that others can empathize with my prose. The bot poetry bothered me because it wasn’t me. It was some bizarro world version of me. In this instance, I wasn’t excited to be published. I didn’t feel like I was sharing any portion of myself or the human experience. Those were words I had owned at one point, words that could once be attributed to me, but their final construction was foreign.

What I’ll Explore at SXSW

One thing is clear, the distinction between originality and simulacra is dwindling. It’s essential that we work to define boundaries as technology and art progress. AI poses challenges to authorship as we conceive of it today. We need a critical imagining of what creation looks like when supplemented by automation. We have to decide if and when computer programs, bots, or programmers themselves, can be given the status of “author.”

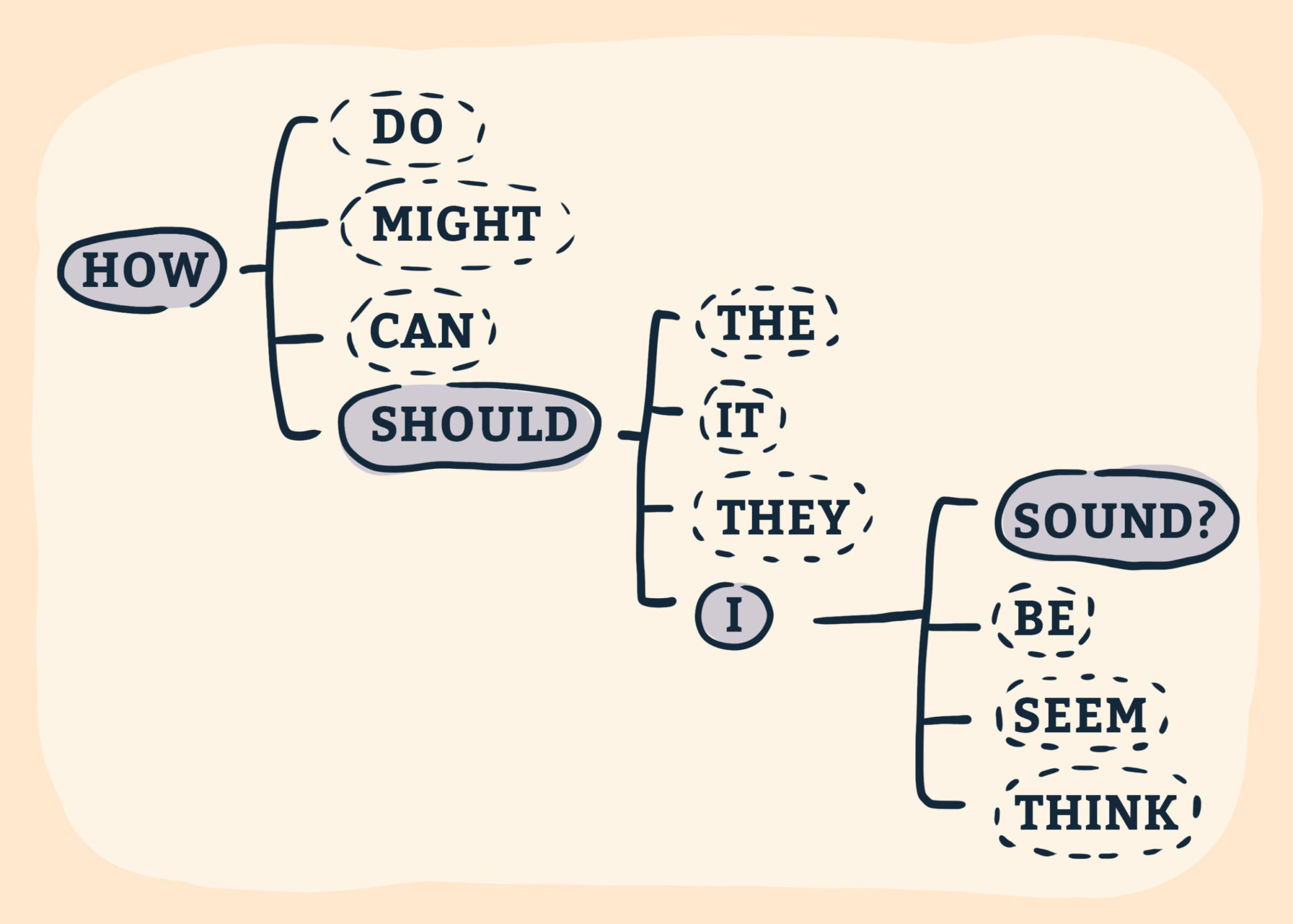

In my talk at SXSW, we’ll discuss strategies for how designers, artists, and UX researchers can use probing questions as a tool for more ethical Natural Language Processing in design and publication. We will discuss the types of questions we can insert into our in-depth interviews, surveys, and research facilitation that allow us to be more thoughtful about potential negative outcomes. Questions like:

- Should an artist’s ownership over their work change by tool?

- Does the final output or media type matter?

- What role does randomness play in authorship?

- If I told you “x” was the primary author of content or artwork, how would you feel? Why?

My talk will also showcase a potential scale or grid that we could use to guide when something should or should not receive attribution. I’ll plot past examples of “randomly generated”, experimental artworks on this grid—things like Mozart’s dice game and John Giorno’s Dial-A-Poems.

See you in March! While you’re there, be sure to check out SXSW talks from my fellow Thinkers Neha Aarwal and Dhiraj Sapkal (Tech-Free Service Design: Mumbai’s “Dabbawalas”) and David Dylan Thomas (Content Strategy Hacks to Save Civil Discourse).

Further Reading:

- Bot or Not Turing test

- Poetry.exe

- Google’s AI has written some amazingly mournful poetry

- Magical Realism Bot

- Concepts Bot

- The Robots are Here to Write Poetry

- Deep-speare: A joint neural model of poetic language, meter and rhyme

- AI-Mediated Communication: Definition, Research Agenda, and Ethical Considerations