The content strategy of civil discourse, part 4

In part three, we talked about how design influences conversation—both in the real world and online. Now we’re going to zoom out a bit to talk about two different approaches to conversation that make all of the difference: collaboration versus hierarchy.

A hierarchical approach basically says, “This is how it should be and there should be no deviation.” It already knows the answer. It is non-learning because, well, what is there to learn? We already know the answer. All we can discuss is whether or not you agree.

It is also exclusive. It divides the world into two groups: those who know the answer and the idiots who don’t. Those who disagree are excluded. Their only hope of inclusion is to agree.

A collaborative approach says, “Here is a problem we can solve together.” It doesn’t have the answer. In fact, it searches continuously for better answers. It is learning by nature. It is learning at all times.

It is also inclusive. It looks at others as potential sources for insight. It doesn’t say, “There’s someone who doesn’t think like we do, let’s shun them!” Instead it says, “There’s someone who doesn’t think like we do, let’s benefit from their perspective!”

Currently, the way we talk about race is, for the most part, hierarchical.

This is the general reaction when someone says or does something insensitive.

This is an important, even necessary, reaction. But it has its limitations.

One shortcoming is that it treats n00bs like trolls. There are some folks who are actively trying to cause trouble and say hurtful things. There are others who are genuinely trying to learn and have a meaningful conversation about race, but are just terrible at it. Social media treats them both the same.

But here’s the thing: speaking meaningfully about race is a skill. You aren’t just born knowing how to do it. Social media treats you like you should. Getting better at a skill requires practice. What happens when you practice? You fail. And Twitter allows no room for error.

The problem with this approach is that knowing how not to do something is not the same as knowing how to do it. If I were trying to teach you how to drive a car and the only thing I did was smack your hand every time you did something wrong, you would never learn how to drive that car. All social media does is smack your hand when you do it wrong.

Here’s another problem. Answer this question:

What’s the opposite of a racist?

If you did come up with an answer, odds are it wasn’t instant and it wasn’t the same answer that 100 other people would come up with. If we don’t have a go-to obvious word for the opposite of a racist, that’s a problem. It’s very difficult to get a thing if you don’t have a word for that thing.

We don’t have the language to describe how to do it right, but we have plenty of words to describe how to do it wrong.

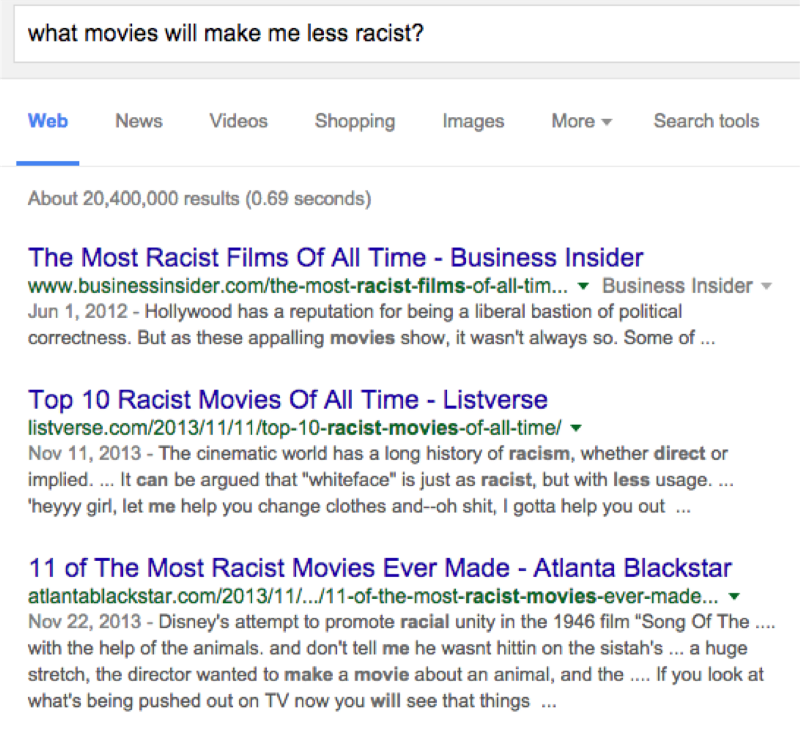

You can get a sense of how little content we have describing the behavior we want by searching for it. A little while ago, I had a podcast about how race is portrayed in different film genres. On a whim, I decided to Google “what movies will make me less racist?” Look what I found…

I got the exact opposite of what I asked for. As a content strategist, I spend a lot of time thinking about what content is available to answer different questions a user might have, and these search results are, on every measurable level, terrible. We have so much much content telling us how to do it wrong that when we ask for content telling us how to do it right, we still get content telling us how to do it wrong.

Again, it’s not that we should stop having should discussions, it’s just that that’s all we ever do. And if that’s all we ever do, the best we can hope for is a bureaucracy. A bureaucracy is a place where you spend all of your time trying to avoid getting into trouble. It’s designed to limit error by punishing failure, not innovate solutions by encouraging understanding.

Another key factor in the inadequacy of hierarchical conversations is a cognitive bias called reactance. Reactance is, by far, one of the wackiest cognitive biases there is, but the short answer is it’s the “you can’t tell me what to do” bias. If I were to put up a sign near one wall that said “Please don’t write on this wall,” and another sign near a different wall that said, “UNDER NO CIRCUMSTANCES SHOULD YOU WRITE ON THIS WALL!!!”, guess which wall would get the most graffiti?

This is why political correctness, as a movement, failed. It was basically a list of things you should or shouldn’t say, which is like catnip to reactance. It just made people want to say insensitive things even more just to show their independence. It failed to communicate a vision or understanding that allowed people to contribute to better, more productive communication on their own.

So, what do we do about it? In our final installment, we’ll stop talking problems and start talking solutions.

Did you know Think Company offers this series as a talk for teams, events, and conferences? If you’re interested in learning more, get in touch with us via our contact form.